Hunter with Harpoon by Markoosie Patsauq

Translated by Valerie Henitiuk and Marc-Antoine Mahieu

Translated by Valerie Henitiuk and Marc-Antoine Mahieu

50 years after the initial publication, this Canadian classic set in the far north has been newly translated directly from Inuktitut, in consultation with Patsauq. Patsauq originally translated his own syllabics into English, but that text was then edited to make it more of a children‘s story (which is how I remember it). Told in shifting perspectives, this new edition, only about 65 pages long, has cinematic energy and a powerful dignity.

They wait a couple of days, but the dogs do not come back. So they start walking, with their belongings and the rest of the food on their backs. As they go along, Kamik draws close to Qisik and asks, “How long will it take to reach our land?”

“Twenty days, I think, if we‘re on the right path.”

“And if not?” Kamik asks again.

“Then we won‘t make it home,” replies Qisik.

“Twenty days, I think, if we‘re on the right path.”

“And if not?” Kamik asks again.

“Then we won‘t make it home,” replies Qisik.

This world is full of beautiful things, he thinks, but it is a world that leaves you very cold and hungry. Then he also sees the northern lights. He wonders what makes them appear and why right here. The world offers beautiful things to look at even as you are starving to death.

Return of the Trickster by Eden Robinson

Audiobook read by Kaniehtiio Horn

Audiobook read by Kaniehtiio Horn

Can Jared stay sweet, sober and committed to nonviolence no matter what horrors he encounters? He‘s one of over 500 offspring of his trickster father, but he‘s still one-of-a-kind. Who else has internal organs who run from his own body? This thrilling conclusion to the Trickster trilogy is a joyride with vicious coy-wolves, helpful inter-dimensional fireflies, otter humans, a gentle sasquatch, and an evil ogress. Indigenous literature like none other.

Hot women, in his experience, did not follow him around, flirting. They were either family, or they wanted to kill him. Usually both.

“There‘s a completely gratuitous sasquatch scene.”

—Eden Robinson (Haisla/Heiltsuk), talking about Return of the Trickster in an interview with Shelagh Rogers on 'The Next Chapter'

—Eden Robinson (Haisla/Heiltsuk), talking about Return of the Trickster in an interview with Shelagh Rogers on 'The Next Chapter'

Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming of Age by Darrel J McLeod

Darrel McLeod is a queer Nêhiyaw from northern Alberta, writing about his loving yet painful relationship with his mother, Bertha. She was severely punished at residential school for speaking her language—by nuns who spoke in a garbled mix of English and French—so she didn‘t want her own children to learn Nêhiyawêtân. Racism, queer identity, cultural and family connections—all crafted in a spiral style and with avian messengers. Mamaskatch received a Governor General literary award in 2018.

The markers for I and you are attached as extra syllables to the verb forms. The second-person pronoun is always more important, so it comes first, whether it‘s the subject or the object. Unlike in English, I love you and you love me both start with the marker ki, for you. The gendered pronouns he and she don‘t exist in Cree. Mother has told me this more than once, laughing at herself for getting the two mixed up.

My interpretation of what I was learning was different from the usual student‘s. For example, Ernst Haeckel‘s theory that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” simply confirmed what my great-grandfather had used to say—that we were all related, the two-legged, the four-legged, those that fly and those that swim.

Initially the principles of existentialism disturbed me, but with time they provided relief. What if there really was no heaven or hell, and I only had to live in the present and make the most of it—accept responsibility for my own happiness and well-being? I loved the notion that I could choose whether or not to believe in Christianity without living in constant angst of going to hell.

O my Jesus, forgive us our sins.

Save us from the fires of hell…

The words cut me to the core—there it was again, hell. Why was the Church so obsessed with hell—why did it need to instill terror into people‘s hearts?

Come Home, Indio by Jim Terry

Jim Terry‘s father was white and his mother Indigenous (Ho-Chunk). Both parents struggled with alcoholism. This moving memoir in comics format documents the artist‘s turbulent childhood and sense of alienation, leading to his own addiction to alcohol. He takes us with him to rock bottom, then to sobriety. Attending the protest at Standing Rock helped bring him home to himself. His brushwork art and rich blacks throughout is reminiscent of Will Eisner‘s work.

We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom and Michaela Goade

Two talented Indigenous women--Lindstrom (Anishinabe/Metis) and Goade (Tlingit/Haida)--created this absolutely gorgeous picture book with an important message: the need to protect our supply of fresh water, on behalf of all living beings. An inspiring call to action.

Ancestor Approved: Intertribal Stories for Kids, edited by Cynthia Leitich Smith

Audiobook read by Kenny Ramos and DeLanna Studi

A wonderful anthology of interconnected stories for kids age 8 and up, all written by different Indigenous authors, all having common elements:

a) the protagonists travel to the intertribal Dance for Mother Earth powwow in Ann Arbor, Michigan

b) the stories include mention of a particular dog who's wearing a t-shirt.

The dancing, regalia, food stalls, craft vendors—these are seen from different viewpoints. The kids, from tribal groups across the US and Canada, portray the vibrancy of indigeneity today. Excellent for family listening.

Love After the End: An Anthology of Two-Spirit and Indigiqueer Speculative Fiction, edited by Joshua Whitehead

Speculative fiction from queer Indigenous authors: these stories are fresh, varied and imaginative. I didn‘t like them equally but I found something to admire in each. I also now have new-to-me authors to watch. Editor Joshua Whitehead‘s introduction is my favourite piece, for its scholarly yet poignant wordplay. The rest are aimed at tween and teen readers, although of course they can be enjoyed by older readers too. The cover art by Kent Monkman (Nêhiyaw) on the revised 2020 edition (Arsenal Pulp) is a perfect complement.

Who names an event apocalyptic and whom must an apocalypse affect in order for it to be thought of as “canon”? How do we pluralize apocalypse? Apocalypses as ellipses? Who is omitted from such a saving of space, whose material is relegated to the immaterial?

(from the introduction by Joshua Whitehead (Oji-Nêhiyaw))

(from the introduction by Joshua Whitehead (Oji-Nêhiyaw))

Here is my first instruction: when the apocalypse happens, make sure you bring your kookum. Mine is named Alicia. She doesn‘t have an Anishinaabe name because when she was born they were only starting to get them back. You‘re going to want your kookum when the apocalypse happens because kookums know everything. Mooshums do too but they can get bossy and think they‘re right all the time, like the council does.

-Kai Minosh Pyle (Mekadebinesikwe)

I ask, “How do we build a relationship with this new planet?”

She laughs. “I would assume like all consensual relationships: we ask them out.”

She laughs. “I would assume like all consensual relationships: we ask them out.”

-jaye simpson (Oji-Nêhiyaw/Saulteaux)

“I don‘t think you can call humans a failure. We built spaceships. We invented vaccines and …” She looked somewhere above my head, presumably scanning a vast imaginary landscape of possibilities. “… and spreadsheets.”

-Adam Garnet Jones (Nêhiyaw/Metis/Danish)

The Sea in Winter by Christine Day

This quiet middle grade novel about letting go of unattainable dreams has many strengths, including a realistic portrayal of a contemporary Indigenous (Makah/Piscataway) family in Seattle, and a fierce but sad central character who is passionate about ballet. I‘m glad the author chose ballet over traditional dance, because it sidesteps stereotypes. The dedication at the front sums up the message: “To anyone who needs a reminder that pain is temporary.”

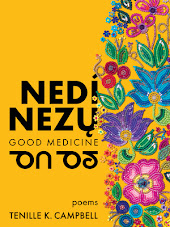

Nedi Nezu: Good Medicine by Tenille K Campbell

When I heard Tenille Campbell (Dene/Metis) read at a poetry event online, I knew I needed this collection. Her sensual poems celebrate lustiness and a large, brown body belonging to a woman who makes her own choices and remembers to look after herself. Words in Dene and Nêhiyaw language reclaim Indigenous space on the page.

when you come to the door

black garbage bag in hand

full of clothes and mismatched socks

underwear she bought you

t-shirts your mom got you

I realize

loving you

would mean loving me less

I fought too hard

to be this version of me

and I‘m not raising

a grown-ass man

again

black garbage bag in hand

full of clothes and mismatched socks

underwear she bought you

t-shirts your mom got you

I realize

loving you

would mean loving me less

I fought too hard

to be this version of me

and I‘m not raising

a grown-ass man

again

No comments:

Post a Comment