Barbara Ehrenreich, an activist, journalist and lifelong atheist now in her 70s, looks back on her teenage self in

Living with a Wild God: A Nonbeliever's Search for the Truth about Everything. In particular, she examines the meaning of a mystical experience recorded in her journal in 1959, when she was 16.

Everyone else in my book group hated

Living with a Wild God. I was taken aback by their reaction, because I loved it so much that I read it twice. I listened first to the audiobook [Hachette: 9 hr] performed by the author, which is always a treat with autobiography. Then I read it in paper. Only one other person - the lone scientist in our group - had even finished the book, and while she admitted that the ending was worthwhile, she found most of it a slog.

At our book meeting last month, my library copy was bristling with flags. I'm going to quote some here for future reference. If you like this sort of thing, I invite you to join me while I revisit a selection of passages. It's somewhat of a marathon. If you haven't yet read

Living with a Wild God, these excerpts should make it clear whether or not this book is for you.

"But if you are thinking this is the usual story of dysfunction and abuse, then I'm doing a poor job of telling it, and projecting my own standards as a parent onto a time, and a class, when children were still regarded as miscreants rather than the artisanal projects that they have become today. It's not easy to explain my parents' complicated role in repressing and inspiring me, clamping down and letting go."

"In the 1950s, when I hit my teens, the 'central developmental task' that psychologists had devised for this phase in the lives of young humans was gradually to put away existential angst and unrealistic ambitions for the benumbed state known as 'maturity.'"

On pondering the meaning of life:

"The reason I eventually became a writer is that writing makes thinking easier, and even as a verbally underdeveloped fourteen-year-old I knew that if I wanted to understand 'the situation,' thinking was what I had to do."

Family outings on Sunday afternoons:

"Sometimes there would be a touristic destination or at least a roadside tavern as a turnaround point, where the grown-ups would have a few beers while we kids waited out front. If I had known that drunk driving carried the risk of maiming and death, these Sunday afternoon enterprises might have been more successful at holding my interest."

Ehrenreich's first mystical experience:

"And then it happened. Something peeled off the visible world, taking with it all meaning, inference, association, labels, and words. I was looking at a tree, and if anyone had asked, that's what I would have said I was doing, but the word 'tree' was gone, along with all the notions of tree-ness that had accumulated in the last dozen or so years since I had acquired language."

"If this was a mental illness, or even just a particularly clinical case of adolescence, I was bearing up pretty well."

Friendless, but not unhappy:

"On the whole, despite family tensions, social isolation, the ongoing horror of puberty, and intermittent philosophical despair, I was not unhappy, or if I was, I did not see fit to write about it. There was too much going on for that, too much to find out and absorb, and emotions were not my natural beat."

Like Ehrenreich, my favourite subject in high school was chemistry. The next passage is another example of why I identified strongly with Ehrenreich as a teenager. She was required to take a

"course brazenly entitled 'Life Adjustment'" at a new school after moving to Los Angeles:

"On about my third session in this course we were given a 'personality test' to fill out, featuring multiple-choice questions about our eagerness to spend time with friends (of which I had none at the moment), eventual interest in marriage, and general satisfaction with the status quo. I filled it out quickly and guilelessly, prepared to learn something about that mysterious doppelganger, my 'personality.' But no, as soon as we had finished the tests, the teacher instructed us to exchange papers with the person sitting across the aisle from us, so that the test could be corrected.

I stuck up my hand to raise the obvious, even platitudinous question: How could there be 'right' answers if, as had just been explained, each person has a unique personality? [...] I got some kind of patronizing answer about my being new to the class and how everything would be clear soon enough. So I stood up without saying another word, picked up my books, and walked out, taking my potentially incriminating test with me."

(At book group, I was surprised to find myself alone in sympathetic outrage over the previous passage. The other women found fault with teen Ehrenreich for not being willing to trust the teacher's process.)

On a skiing trip at age 16 with her school friend, Dick, and her brother:

"[Dick's inexplicable] anger shamed me into silence, suggestive as it was of some sort of intimacy. As far as I had ever been able to determine, anger was the principal emotional bond between husbands and wives and possibly the only thing that held them together."

"I should have stayed home and read Kafka, whom I'd just discovered in a paperback bookstore and found agreeably disorienting."

"Dick's looks were not lost on me, but I didn't aspire to be his or anyone's girlfriend. If anything, my secret, inadmissible craving was to be a boy like him or at least some sort of gender-free comrade at arms."

On her relationship with her father:

"I know I was not his actual son, only a botched reincarnation in which his magnificent genius mind had been misplaced in a female body, where it was dragged down and eroded by the hormonal tides. I was supposed to be smart, like him, but never as smart as him. I was supposed to ask questions, but only answerable ones that gave him a chance to demonstrated his superior logic and education."

Later, Ehrenreich writes of her fear of

"the dark, swampy side of female existence."

Ehrenreich, an atheist from childhood, writes about a key mystical experience in 1959:

|

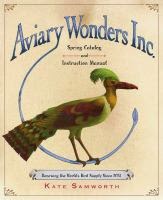

Interior column in

Les Jacobins, Toulouse,

reminds me of a

burning bush. |

"Here we leave the jurisdiction of language, where nothing is left but the vague gurgles of surrender expressed in words like 'ineffable' and 'transcendent.' For most of the intervening years, my general thought has been: If there are no words for it, then don't say anything about it. Otherwise you risk slopping into 'spirituality,' which is, in addition to being a crime against reason, of no more interest to other people than your dreams.

But there is one image, handed down over the centuries, that seems to apply, and that is the image of fire, as in the 'burning bush.' At some point in my predawn walk - not at the top of a hill or the exact moment of sunrise, but in its own good time - the world flamed into life. How else to describe it? There were no visions, no prophetic voices or visits by totemic animals, just this blazing everywhere. Something poured into me and I poured out into it. This was not the passive beatific merger with 'the All,' as promised by the Eastern mystics. It was a furious encounter with a living substance that was coming at me through all things at once, and one reason for the terrible wordlessness of the experience is that you cannot observe fire really closely without becoming part of it. Whether you start as a twig or a gorgeous tapestry, you will be recruited into the flame and made indistinguishable from the rest of the blaze."

Then there was a "post-epiphany crack-up."

"Would religion have saved me, if I had one or could have adopted one? Years later, as an adult, I read in one of the women's magazines I wrote for at the time an article that actually dealt with the subject of 'mystical experiences.' These could be unhealthy, even shattering, the writer averred, unless a person had a religion in which to 'house' them. This was the function of religion, in fact - to serve as a safe storage space for the unaccountable and uncanny."

God is not good:

"If there was one thing I understood about God, it was that he was not good, and if he was good, he was too powerless to deserve our attention. In fact the idea of a God who is both all-powerful and all good is a logical impossibility - possibly a trap set by ancient polytheists to ensnare weak-minded monotheists like Philo and Augustine, and certainly not worth my time."

Ehrenreich gives thanks that her grandmother sent an electric frying pan as an early wedding gift, because its implications made her rethink the realities of an impending marriage when she was 19, and to call it off. Her fiance, Steve, took the news

"fairly stoically, for which I count myself lucky, because he later received a twenty-three-year prison sentence for the attempted murder of the woman he eventually married, who had, according to the local Eugene newspaper, made the mistake of asking for a divorce."

"I spent the first few months of graduate school pretending to be a student of theoretical physics. This required no great acting skill beyond the effort to appear unperturbed in the face of the inexplicable, which is as far as I can see one of the central tasks of adulthood."

On remaining open to mystic possibilities:

"Mysticism often reveals a wild, amoral Other, while religion insists on conventional codes of ethics enforced by an ethical supernatural being. The obvious solution would be to admit that ethical systems are a human invention and that the Other is something else entirely."

_Bacteria.jpg) |

Staphylococcus aureus bacteria

(via National Institutes of Health) |

"Monotheism inhibits us from imagining anything involved with the 'numinous' or 'holy' as part of a species, since a species generally has more than one member. But if the hypothesized beings are 'alive,' that is, technically speaking, what we are dealing with.

As for those who insist on a singular deity, I would note that the line we draw between an individual and a multitude is not always clear: Slime molds can exist as individual cells or join together to form a single body; bacterial colonies can exhibit a kind of intelligence unavailable to individual bacterial cells. [...] If there seems to be some confusion here on the subject of case - whether to say Other or Others, deity or deities - it grows out of the limits of our biological imagination."

Living with a Wild God is a powerful book for the right reader, especially one who felt the tension between logic and faith from an early age. My book group experience reveals that it isn't for everyone, but I recommend it anyway. It sparked discussion about spirituality, about memoir in general, and about women in science.

_Bacteria.jpg)