November stats: 41 books; and 26 of them were outstanding. I get fussier as I age so I will only read those books I think I will love. As a result, I read so many great books in November that I decided to break up my monthly round-up into three parts. The first part was yesterday, all audiobooks. Tomorrow will be all LGBTQ. And today is for the rest!

Everything Affects Everyone by Shawna Lemay

Be kind to yourself. Read this compassionate novel by multitalented Edmonton poet and photographer Shawna Lemay. Read it slowly. Within it, six women have conversations and contemplations about art, and about how best to live. Before the first page, its philosophical and experimental bent is revealed by the epigraphs, which are by the likes of Clarice Lispector, Hélène Cixous, and Rainer Maria Rilke. Later, Alan Watts is quoted on the distinction between belief and faith. I learned that the word angel comes from the word for messenger. I learned that angels eat Fruit Loops and whipped cream. I also learned it was impossible to rush through this book, because I kept stopping to savour the language and the ideas.

Everything will be okay. This is what I tell myself, and I think about what a good, sweet word is “okay.”

I want to know what characters are thinking and how they attempt to speak what‘s in their soul, honestly and simply. Or, alternatively, how they circle around things, how they attempt to conceal, or how they fail to express what they mean to convey.

The way we come to a conversation matters. The openness, the trust. Is every conversation a type of annunciation? Each person is an angel giving the other person, who is also an angel, a message. In that moment we are each responsible for the other. If one of the people in the conversation were to faint or to cry, for example, it would be up to the other person to act.

The angel bows to Mary and announces her fate. And some of what‘s happening in the image continues to speak to me. The deep bow of respect. The acknowledgment of beauty of another human being, the strength and endurance. The potential. Acknowledging the light in another being. Bowing to that light.

All of those artists painted angels, or found angels, and who‘s to say they didn‘t see or feel them? For me, it wasn‘t a question of belief in angels, but it was about a willingness to see what is there, and to witness the world with a deeper awareness. But also, to be open to the unseen world.

It is the questioning around the story that gives the story its dimension. But the story is there only as a kind of basic pretext.

There is an ongoingness that I wish to convey. The traditional narrative arc is wonderful, but it is not the only mode in which to talk about how things occur, how life rolls out, how life comes at us and is so boring and delightful at once, so unpredictable and so obvious, so weird and so lovely and hidden and open.

The air and the atmosphere are a miracle. We don‘t have to look around for examples of the miraculous; we need merely to breathe in and out, or move our hands through the air, the wind.

I like reading diaries better than novels, and better than watching movies. Diaries are life, you see. And life can be rather dull. Rather ordinary. If I have learned one thing, it is that the ordinary is more closely aligned with bliss and to splendour than to what might be deemed spectacular.

I know how to make myself appear completely ordinary so that I might observe others. What I observe is that not a single person on this earth is ordinary.

I was thinking about something so beautiful that I entered the silence of flowers.

The Years by Annie Ernaux

Translated by Alison L Strayer

I felt like I was swimming through time in company with French author Annie Ernaux, who intertwines personal and societal experiences in this memoir/cultural history spanning seven decades. The voice shifts between “she” for the author and “we” for the collective, managing to be both intimate and expansive. Not every detail (ie French politics) resonated, but I identified strongly with the changing landscape of women‘s lives and the rise of consumerism.

By their clothing, we could distinguish little girls from young girls, young girls from young ladies, young women from women, mothers from grandmothers, labourers from tradesmen and bureaucrats. Wealthy people said of shopgirls and typists who were too well dressed, “They wear their entire fortune on their backs.”

With the Walkman, for the first time music entered the body. We could live inside music, walled off from the world.

The USSR disappeared and became the Russian Federation with Boris Yeltsin as president. Leningrad was St Petersburg again, much more convenient for finding one‘s way around the novels of Dostoevsky.

Only teachers were allowed to ask questions. If we did not understand a word or explanation, the fault was ours.

But for the first time, we envisioned our lives as a march toward freedom, which changed a great many things. A feeling common to women was on its way out, that of natural inferiority.

Of all the information we received daily, the most interesting, the kind that mattered most, concerned the next day‘s weather. The rain-or-shine monitors in the RER stations displayed predictive, almanac-style knowledge that provided us with a daily reason to rejoice or lament, thanks to the surprising and yet invariable factor of weather, whose modification by human activity profoundly shocked us.

Under the spell of media simplifications, people believed in the technological delicacy of bombs, “clean war,” “smart weapons,” and “surgical strikes”: “a civilized war,” wrote Libération.

Under Giscard d‘Etaing we would live in an “advanced liberal society.” Nothing was political or social anymore. It was simply modern or not. Everything had to do with modernity. People confused “liberal” with “free” and believed that a society so named would be the one to grant them the greatest possible number of rights and objects.

Television sets were turned in for newer models. The world looked more appealing on the colour display, interiors more enviable. Gone was the chilly distance of black-and-white, that severe, almost tragic negative of daily life.

The word “struggle” was discredited as a throwback to Marxism, become an object of ridicule. As for “defending rights,” the first that came to mind were those of the consumer.

Invisible North: The Search for Answers on a Troubled Reserve by Alexandra Shimo

Lesbian journalist Alex Shimo had permission from the band chief to live on the reserve and document the story of unsafe water at Kashechewan in northern Ontario. But too much didn‘t make sense. Was it a hoax? Yet the shocking living conditions, the dire poverty—Shimo could see there was an important story to share with non-indigenous Canadians, but she struggled to maintain her mental equilibrium there. Words can hardly express how profoundly moved I was by this book.

This is where Canadian history differs from that of other developed countries, such as the United States and New Zealand, which also committed mass displacement of their Indigenous populations, but mostly stopped after the 19th century. As a result, Canadian First Nations have less land compared to those in other developed countries. For example, in the United States, Native Americans account for 2 percent of the population and reserves account for 2.3 percent of the total land. In New Zealand, Maoris account for 14.6 percent of the population and own 5.5 percent of the country. By contrast, Canadian Aboriginals make up 4.3 percent of Canada's total population, while reserves account for 0.2 percent of the nation. This, although Canada is an underpopulated, sprawling country near the size of a continent, with a land mass larger than the size of the United States and a population one-tenth the size.

Manikanetish by Naomi Fontaine

Translated by Luise von Flotow

Yammie left her Innu reserve, Uashat, on Quebec‘s North Shore, when she was a child. She returns 15 years later as a high school teacher. This quiet yet powerful novel documents a year of her experiences, connecting with her troubled but remarkable students, who face nearly insurmountable challenges. Meanwhile, she sorts out her own feelings of belonging to the place. This book pairs well with Shimo's Invisible North, because of the teenagers and the school situation in both.

An old, very wrinkled woman wearing the traditional Innu red-and-black felt bonnet. Not bothering to look directly at the camera. I was told later on that the missionaries were the ones who made Innu women wear the bonnets and keep their hair in braids rolled up on the sides of their heads and pinned at their temples. Because, with their long hair caressing their backs au naturel, they were beautiful. Attractive. Savage. Too beautiful for men of God and their oath of celibacy. They made them ugly.

Journal of a Travelling Girl by Nadine Neema

This remarkable chapter book for children (Grades 4-6) honours the traditional ways and stories of the Tłįcho people as well as a landmark historical moment in Canada: the signing of the Tłįcho land and self-government agreement in 2005. The action—external and internal—takes place through the eyes of 11-yr-old Julia while on an important canoe trip. Simple line drawings by Archie Beaverho accompany and enrich the text.

At the start of one of the portages, we saw a bird‘s nest that was so perfect it looked like a precious piece of art that someone had made for Easter. Inside, there were eight or nine eggs. It was just sitting there by itself in the long swampy grass. Grandma told us they were duck eggs. I couldn‘t believe that was made by a duck.

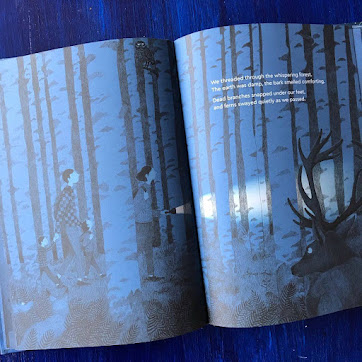

The Night Walk by Marie Dorleans

Translated by Polly Lawson

Many families turned to the solace of time spent in nature during the pandemic. Whether or not this activity was actually possible for readers of this endearing picture book, its portrayal of a quiet nighttime adventure is very inviting. There‘s also a natural propulsion: an unknown but important destination. A perfect laptime book: enjoy it slowly, studying the detailed pencil illustrations and seeking out the various nocturnal creatures. The art is understated, yet magical. Which is a feat, considering that the whole of the action takes place in the dark, and the story remains realistic, not drawing on any fantasy elements.

We threaded through the whispering forest. The earth was damp, the bark smelled comforting. Dead branches snapped under our feet, and ferns swayed quietly as we passed.

Mel Fell by Corey R Tabor

One of the many great things about this children‘s picture book about an intrepid young kingfisher is the orientation: the pages are designed to be viewed vertically instead of horizontally, and at one point in the story, the reader is instructed to flip it around with the opposite end up. Great manipulation! And it's also an inspiring story about bravery and community spirit. The appealing art, created with pencil and acrylic, is bright yet simple.

Love from A to Z by SK Ali

I was not thrilled that my YA bookclub chose this title, since I am not a fan of romance. I‘d read Toronto author SK Ali‘s Saints and Misfits previously and it was okay, but I have little patience these days for books that I am not passionate about. I confess that I was pre-hating this book. I decided to just read enough of it to be able to join in the discussion. Then, I got sucked into the story. Wow, was I ever wrong about this book!

Believable characters. That's why I loved this YA romance even though I normally despise romance. Zayneb takes action in the face of bullshit and injustice. Adam is quiet and considerate. Islamic faith is satisfyingly woven into the narrative in an ownvoices way. I wept at a stranger‘s kindness, then at the description of MS symptoms, but didn‘t feel like the author was toying with my emotions. I guess “believable” is the key word here. I cared.

Everyone has a different definition of what “doing your best” means. For Mom and Dad, it means not rocking any boats.

For me it means fixing things that are wrong.

The Look of the Book: Jackets, Covers and Art at the Edges of Literature by Peter Mendelsund and David J Alworth

I have always been interested in book covers—I use them to judge contents like most readers do—but after reading this, I‘m hyperaware. Graphic designer Peter Mendelsund and scholar David Alworth collaborated on this heavily-illustrated investigation into the cover art on literary fiction. The way cover design first grabs our attention; how it frames and even shapes our reading experience; and the tricks or techniques used to translate verbal art into visual form. Love!

Like a bag of potato chips or a television commercial, book covers have an obvious mandate, which is to sell a commodity, except in the case of literature the commodity is also art.

Announcing the text and creating a conduit between imaginary and real space are two key tasks of the book cover. They are what the book cover does, first and foremost, but they are not all that it does. The cover‘s job is not over when you begin reading the pages. A good book cover has that time-release quality: it changes with you as you read.

If a book contains a map, it is likely either military history or fantasy—or Faulkner, which is both. Certain paratextual details, in other words, are indicators of genre: they tell you what kind of book you hold in your hands.

“A great book cover is, for me, like a great Spanish edition. The designer takes the manuscript and deftly translates it into a language I understand but am unable to speak with any clarity. ‘How on earth did you do that?‘ I think when I‘m given the finished product. To take 70,000 words and turn them into a single image. How is that not a miracle?”

—David Sedaris

Author Teju Cole insists that we push back against the “epidemic of relatability” that has besieged book culture. “It‘s like everybody wants to be ‘fun,‘ but not all books are ‘fun.‘”

No comments:

Post a Comment