Here are some highlights from my reading in October. If you want books by Indigenous authors, check out yesterday's Indigenous Books Bonanza.

The Barnabus Project by the Fan Brothers

Barnabus, a genetically engineered half mouse, half elephant, makes a dramatic escape from the failed experiments shelf, and saves a bunch of others too. All three of Toronto's Fan brothers (Eric, Terry and Devin) collaborated to create the digitally coloured graphite illustrations that reward lingering over details in this magical picture book. Best of all is the beautiful message of inclusivity. Winner of the GG (Juvenile Illustration) and the TD Canadian Children‘s Literature Award.

The Wind and the Trees by Todd Stewart

Framed as a conversation between two trees across the years, this Canadian picture book is a quiet masterpiece about the cycle of life. Todd Stewart‘s silkscreen art is simple and striking. The background colours shift with each page turn, capturing many moods. Birds and animals add drama, also changing with each page turn: a treasure hunt for young readers. The interconnectedness of all is a comfort for readers of any age.

A Dream of a Woman: Stories by Casey Plett

Quiet, acute and bittersweet. I highly recommend this Giller longlisted collection featuring trans women who are as real as real can be. They deal with ordinary adult concerns—jobs, longtime addictions, looking for love that will last—complicated by their unique experiences of being trans. One of the stories is a novella split into 5 chapters, interleaved with the other stories, a style decision which is somehow more effective than reading it of a piece.

Truth was, you could be trans and not pass, and this might suck, but it didn‘t make you any less trans or less of a woman. You could be trans if it made you a homo, be trans without taking hormones, be trans and keep your old friends if they weren‘t dicks, be trans and keep your dick, be trans if you wanted to be out about it, for God‘s sake. You know what being stealth does to your soul?

Her inner conception of her appearance is amorphous and difficult to describe, but if she had to try, she might say it is of something masculine without a face, a muscular crush of feathers travelling through a room.

Some people say it was Menno shit, or small-town shit, but Gemma knows better. None of it‘s special. There‘s a line in a book by Miriam Toews herself: “It‘s just something that happens sometimes, a story as old as time, and this time it happened to me.”

“That‘s the thing,” Robyn had said softly. “After a certain age, bio family is chosen family, too. You choose to keep it up—or you don‘t. Both kinds can be unhealthy. Both kinds can be good. And you‘re never obligated to do a thing to someone who isn‘t good to you. Ever.”

We were sold that what‘s written on the internet was forever, but the fact is, so much of it was impermanent daydreams and abysses, gone the second you forgot how to look it up or the owner deleted it or unfriended you, or it lived on a remote subdivision that the Wayback Machine just wasn‘t meant to capture.

Was David gonna transition? Who fucking knew? Not him. It was a scary thought. For years, he‘d spent nights on the internet, discovering how one went about this. And every night, he‘d gone to bed blocking out more fears than he‘d started with. The spectre of poverty and rejection and violence alone were enough to instill an understanding in his body: You only do this if you‘re 300 percent sure.

Glorious Frazzled Beings by Angelique Lalonde

How do I tell you about the cumulative impact of these fierce yet whimsical stories? They are about home and motherhood and sisterhood and womanhood… alongside teeny tiny ghosts, a fox shapeshifter, a supernatural gardener… The charming elements are mixed with profound statements like: “I am good at pretending I know how to be where I am on this land I own that does not belong to me.” I absolutely love this Giller-shortlisted book.

The little fly on my nightstand puked all over my journal. I was so upset I messaged its mother, but its mother was dead because she had already lived out her long 15 days on earth by the time I was able to track down her number.

She frazzled in the bowels of her grief for a good long while, coming out somewhat composted on the inside. No longer so lithe, no longer so young, Carmen had more layers to her. A soil test would have told her she‘d become a more balanced ecosystem, ground in which greater diversity could thrive.

We learn such confidence from books, feeling like if we just look in the right place, the thing that brought us happiness will be there again, waiting, every time we turn the page back to where it was the last time!

You understand motherly sacrifice and motherly overwhelm. Motherly exasperation and motherly joy. You understand the big fat food duty and pending outbursts of the improperly fed, the overly tired, the wired-up or disconnected, the greedy little wanting-everything-for-yourself hatefulness of family. The untidiness of calling all of this love.

Maybe I am like others like me—an accident or designed outcome of the generations that came before. Left here with garbled stories because each generation tries to efface or correct the stories of the last in our attempts to settle ourselves.

Finances make her want to hide in her little shell and do turtle things until all the talking is over.

So cold in the desert night, her inner fire just a bare ember, spirit body needing spirit fire to ignite, keep herself going through this world. Knowing water alone would just freeze, that‘s how cold her insides were. Dump a good dose of whisky in the first glass, hot wetness to drown out dry nerves.

If you asked she would tell you that she loves him like a sheep loves clover: wrapped into its tongue and pushed sideways, mashed into sweet liquid green and fibre in the crush of its grinding teeth.

em by Kim Thuy

Translation by Sheila Fischman

The forward movement from character to character, chapter to chapter, would be dizzying if not for Kim Thúy‘s pure, spare prose that clearly shows the links, establishing order amidst the chaos of the war in Vietnam. True events, especially the My Lai massacre and Operation Babylift—are central to the story. I wept. Love is the antidote to trauma and this Giller-longlisted novel is full to the brim with love. A balm for the heart. Impeccable translation by Sheila Fischman.

If I knew how to end a conversation, if I could distinguish true truths, personal truths from instinctive truths, I would have disentangled the threads for you before tying them up or arranging them so that the story of this book would be clear between us.

During her visit to a camp in 1975, Tippi Hedren, actress in the Alfred Hitchcock film The Birds, received compliments from the Vietnamese refugees for her impeccable fingernails, which gave her the idea of organizing a manicure class for 20 or so women. Her first students, new Californians, passed their knowledge on to 60 more, who themselves trained other manicurists and so they multiplied, becoming 360, 3060 and more.

Upon arrival at their destination, the coolies worked as hard as beasts on sugar cane plantations, down in mines, building railroads, often dying before the end of their 5-year contract without having received their promised and longed-for salary. Companies involved in the trade assumed beforehand that 20, 30, or 40 percent of the “lots” would perish in the course of the voyage at sea.

During the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 and the following year, the rate of infections contracted sexually by the troops grew from less than four percent to more than seventy-five percent, which later led, during the First World War, to the German government‘s giving high priority to the production of condoms to protect its soldiers, even though there was a serious shortage of rubber.

Certainly, bullets kill, but so, perhaps, does desire.

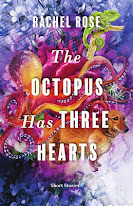

The Octopus Has Three Hearts by Rachel Rose

Do you love stories about odd people? Do you love stories about animals? Then this Giller longlisted collection is for you! Animals and people and some weird situations with very real emotions. And so much heart!

“Do you have a title yet?' asked Mandy. “How about The Goat Whisperer?“

“Not bad, Mandy, not bad. But I think I'll call it G is for Goat.“

“Well, isn't that a little obvious?“

“Exactly. Keep it simple. This English lady wrote a bestseller, H is for Hawk. I read it. Nothing happens except she is alone and depressed and lives with this hawk that she feeds bits of torn-up rabbit and trains to hunt. My book will be way, way better.“

Binge: 60 Stories to Make Your Head Feel Different by Douglas Coupland

Audiobook [6 hr] read by the author and about 18 other narrators, many of them well-known

Apparently, this collection of flash fiction is called 'Binge' because you can‘t read just one. Apparently, I found them addictive because I listened to the entire audiobook twice! The darkly funny tales are tangentially interconnected—through characters; Rubbermaid bins; classic muscle cars; noravirus, SARS and covid; murder… Also, I‘ll never look at cargo carriers on cars the same way, so the subtitle about changing my brain is true. The stories are intimate, and as if told by many different people; the audio production with multiple narrators works really well.

I realize this isn‘t even an actual story, with a beginning and end, I‘m telling you here. It‘s bits of autobiography. But if our lives aren‘t stories, what are they? Glorified microbes on a Petri dish?

For six months or so after my recovery, the people where I worked were greatly relieved when I telecommuted. Telecommuted. Boy, what an old-fashioned word that is. I worked from home.

I didn‘t dread sex, but pleasure-wise, it rated somewhere around having to vigorously use a coal tar shampoo to get rid of lice. Just something you have to do.

In the 1950s they were dropping bombs like firecrackers all over Nevada. In the casinos, they‘d announce the blasts so the gamblers could go outside to view the mushroom cloud. It was fun! But if you dropped one small nuke now people would freak out like little babies and run around suing whoever they could and, I don‘t know, getting hysterical thyroid cancer

Paul at Home by Michel Rabagliati

Translation by Helge Dascher and Rob Aspinall

Multi-award-winning Quebec cartoonist Michel Rabagliati captures the humour of daily life in his series of graphic novels about Paul. I believe this is the sixth one, and it‘s definitely his most poignant. Paul, who hates change, must come to terms with aging and loneliness. I especially love the portrayal of Paul‘s little dog companion, Cookie. Paul at Home is currently a finalist for the 2021 GG Translation award.

The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

“What makes a person want so much? What gives things the power to enchant, and is there a limit to the desire for more?” This fable-like novel draws on Zen wisdom, speaks through a talking book, and balances seriousness with whimsy in a story about psychic diversity, social justice, and our emotional attachment to objects. If you believe the public library is “a shrine of dreams” you may be as enchanted by this book as I was.

This historic image, dubbed the Blue Marble, became a symbol of the environmental movement and caused a profound shift in the way people conceived of the planet, shrinking it from something incomprehensibly immense and awesome into a fragile, lonely orb that you could cradle in the palm of your hand or crush beneath a careless heel.

She wanted to tell them, Your life is not a self-improvement project! You are perfect, just as you are!

Immersed in the minuscule details of daily living, we believe our lives to be separate & our selves to be separate too. But this is a grave delusion. The truth is that everything depends on everything else.

Of course the solution was quite simple: people just had to stop buying so much stuff, but when she mentioned this on a recent call with the American producers […] asking her not to talk about: consumerism, capitalism, materialism, commodity fetishism, online shopping and credit card debt. Speaking critically of such topics was un-American, they explained. American consumers wanted proactive solutions. Not buying was not proactive.

"Let me tell you something about poetry, young schoolboy. Poetry is a problem of form and emptiness. Ze moment I put one word onto an empty page, I hef created a problem for myself. Ze poem that emerges is form, trying to find a solution to my problem."

“Hasn‘t a book ever made you cry?”

He thought about ‘Medieval Shields‘ and ‘Byzantine Garden Design.‘ “No.”

“Okay, wow. Well, maybe you should try reading different books.”

Over the summer, he‘d become familiar with the patrons and staff, and learned how the rhythms of the Library fluctuated during the day. Early mornings belonged to the seniors: the elderly men in threadbare jackets, hovering over the newspaper pages like patient old herons; the gray-haired ladies in tracksuits and sun visors, perched like pigeons on the edges of their chairs.

Disorientation: Being Black in the World by Ian Williams

Audiobook [6 hr] read by the author

Ian Williams reads his own audiobook with warmth and humour. It's a collection of essays about his experiences of anti-Black racism in Canada. They‘re examples of systemic barriers as well as person-to-person interactions, often nonverbal. From childhood onward, all the negative ways that Williams has been made aware that he is different have shaped his sense of self and continue to take a toll on his state of mind. He quotes from writers like James Baldwin, Audre Lorde and Claudia Rankine. He says encouraging things like: “Hope lies in caring for something beyond the self.” It‘s a thoughtful conversation-opener for non-Black Canadians.

The cost of choosing a path that leads you through elite schools and respected jobs is lifelong alienation. You become a kind of Black person who is kind of Black.

Its kindergarten report card would say: Whiteness is encouraged to regulate its emotions and behaviour. Whiteness is encouraged to share. Whiteness is encouraged to play nicely with the other children.

The Air Year by Caroline Bird

I was enthralled by the slightly mysterious meanings and the sheer energy of imagination in the poems in this award-winning collection. They are full of dark humour and are about desire, intimate lesbian relationships, and going through hard times. It's invigorating! Winner of the Forward Prize (Best Collection) and shortlisted for the Costa Poetry Award.

I haunt my own home, silent but for the buzzing / of the fridge with the wine in it, with the secret / light no one can see until they open the door.

You were so beautiful I felt a commotion in the pit of my throat / like my words were fighting over you.

Full Spectrum: How the Science of Color Made Us Modern by Adam Rogers

A fascinating book of popular science that begins 400 million years ago with the geological forces that made titanium and ends with futuristic colours that exist only in our heads. (Pixar mind manipulation!) And remember all the fuss about The Dress? Was it blue-and-black, white-and-gold, or some other colours? Rogers wrote about The Dress in Wired in 2015 and says that over 38 million people read it. (Me included.) Across the centuries, people have worked hard to widen our art palette and solve the puzzle of colour vision—Newton even stuck a giant needle in his eye for the sake of knowledge—and Adam Rogers has an engaging way of writing about all of it.

We learn to see, and then we learn to create, and then we learn more about how we see from what we‘ve created. It‘s a grand oscillation between seeing and understanding.

Carbon‘s ability to stick to all kinds of other atoms in all kinds of ways is what makes “organic chemistry” organic. Be grateful for carbon‘s profligacy; that‘s life, as the saying goes.

Nobody makes colours alone. Nobody sees them without a context, without a contrast or a constant, without geology and biology and history and chemistry and physics. We all make colours together.

[…] we just have to tacitly agree that when I say “blue” you know what I mean […]. Colours may be less about cognition and more about communication.

The single most important thing that determined how you saw The Dress was how your brain identified, unconsciously, the colour of the light illuminating the image—maybe even what time of day you thought the picture was taken. The Dress undermined or outright broke almost every assumption scientists had about colour constancy and the daylight bias of human vision.

The cargo of the Belitung wreck [c 826 CE] redefined the history of colours as commodities, their materiality & technology as valuable as gold, silk, or spices. The way people made & used those colours was the era‘s highest of high tech. And the delivery mechanism was literally hardware, the killer app of the day: porcelain.

You‘ve probably heard of other Chinese inventions—gunpowder, movable type, the needle compass, paper money. Porcelain predated all of that, and was every bit as important, technologically and culturally as significant, as silk and ink. Northern white and southern celadon were two of China‘s greatest exports, the products of an almost magical technology.

No comments:

Post a Comment